Reynard the Fox Is On the Prowl Again

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Great Britain in Reynard the Fox, a masterpiece of medieval Dutch literature. The sly fox, whose antics enraptured readers for centuries, now plays the leading role in several animations, exhibitions and new books.

One of history’s greatest storytellers, the Greek Aesop (6th c. BCE, perhaps a slave), was, and still is, famous for his animal fables – some 250 simple, strongly oral, often satirical tales, commonly of two animals in conversation, making a social or moral point, immensely popular until today. Of particular interest are his twenty-five fables on ‘the fox’. As both character and narrator, the appeal of the silver-tongued fox was such that many listeners came to believe it was he who taught Aesop the animal lore in his tales – a scene depicted in an ancient Greek drinking cup (+ 460 BCE; around the time when his fables were first written down), today in the Etruscan Museum of the Vatican.

Aesop talks with a fox from one of his fables, on a medallion from a Greek drinking cup, exhibited in the Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican.

Aesop talks with a fox from one of his fables, on a medallion from a Greek drinking cup, exhibited in the Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican.© Alinari/Art Resource, New York

Now fast forward 1,500 years to north-western Europe. There, out of a thriving culture of multilingual contact and exchange, a new dynamic emerged in telling animal fables – this time around a fox called Reynard. In Flanders in 1148 master Nivard of Ghent wrote his Latin Ysengrimus, a satirical series of bust-ups between the wolf and the fox. Three vernacular versions followed: first in French (in 1174 the Roman de Renart, among others by Pierre de Saint-Cloud from Normandy); then in German (in 1189 Reinhart Fuchs, by Heinric der Glichesaere from Aix-la-Chapelle); and around 1260 in Dutch, by Willem (about whom we know nothing), whose Van den Vos Reynaerde was translated back into Latin as Reynardus Vulpes in 1275.

Reynard on the cart of a fishmonger who has presumed him dead – meanwhile, the fox is working his way through the stock of fish. Source: The Romance of Reynard and Isengrin, 1339

Reynard on the cart of a fishmonger who has presumed him dead – meanwhile, the fox is working his way through the stock of fish. Source: The Romance of Reynard and Isengrin, 1339© Bodleian Libraries, Oxford

Of this Reynaert

the medievalist Frits van Oostrom said (in Hermans’s A Literary History of the Low Countries, 2009: 27): “Many regard this poem today as the greatest masterpiece of medieval Dutch literature, the prime text to read from this period and one that can be enjoyed without the need for complicated literary-historical explanations.” In 2009, this Dutch Reynaert was published by Amsterdam University Press with a new English translation (in verse) by Thea Summerfield. We also have a range of creative retellings in modern Dutch, and in 2020 its enduring popularity, as one of fifty “essential works of literature in Dutch”, was confirmed by its inclusion in the new Canon of Dutch Literature.

Illumination of the 1581 manuscript of the Roman de Renart

Illumination of the 1581 manuscript of the Roman de Renart© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

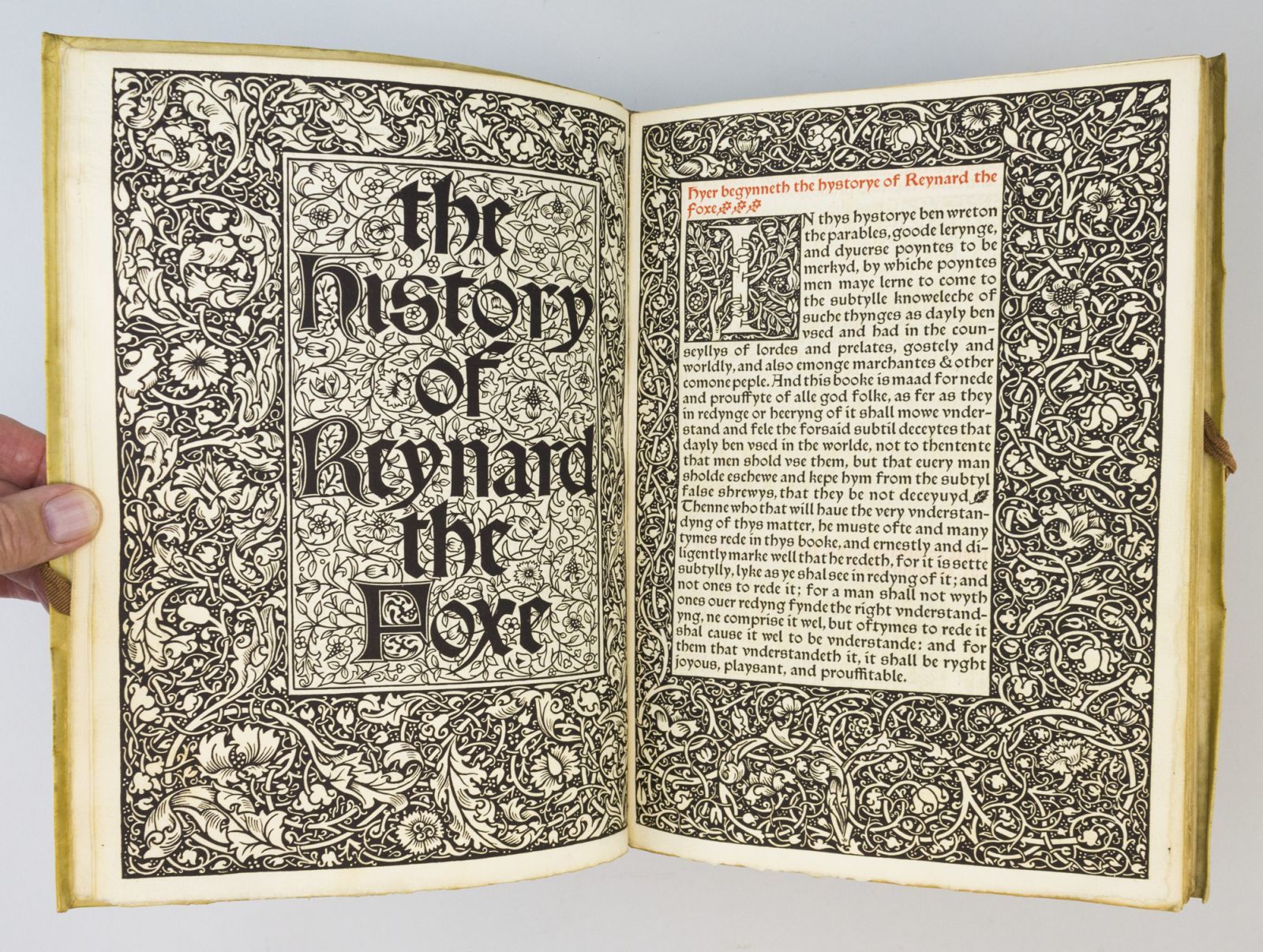

In English, the fox’s literary genealogy began in 1386, when England’s first great poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, in his Canterbury Tales included ‘The Nun’s Priest’s Tale’ (in verse) of Reynard and Chauntecleer the Cock who, falling for Reynard’s flattery, comes to a bad end. Then, in 1481, England’s first printer, William Caxton, published a complete translation (from Middle Dutch) of The

Historye of Reynard the Foxe (in prose), which – through many editions and retellings – has remained popular to this day.

Kelmscott Press edition of William Caxton's History of Reynard the Fox(e), 1892

Kelmscott Press edition of William Caxton's History of Reynard the Fox(e), 1892© pirages.com

Online since 2003, Henry Morley’s 1889 edition of Caxton’s Reynard is available in The Medieval Bestiary; while in 2015 a new translation into contemporary colloquial English was published in New York by Harvard professor James Simpson, with a preface by Stephen Greenblatt. Thus we see how today, both in the Low Countries and far beyond, people everywhere do like this medieval beast epic in which the cunning fox outwits and holds his own against all comers.

Renewed interest

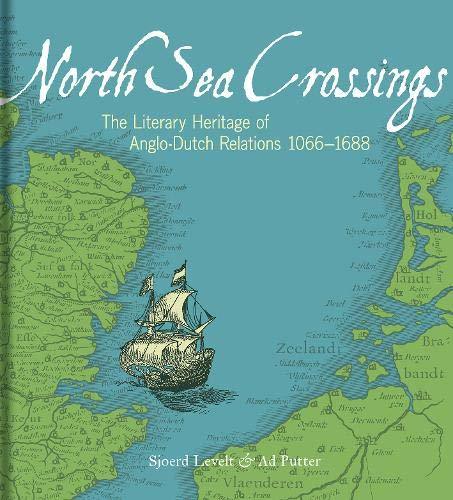

From 2017-18 onwards, there has been an exciting new development around Reynard in Great Britain: the North Sea Crossings project – sponsored by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, a collaboration between the universities of Bristol and Oxford, animation studios Aardman Animations (the creators of Wallace & Gromit), the Bodleian Libraries and the Flash of Spendour

initiative for special education innovation in Oxford. So far, this four-pronged project has given us: a new scholarly impulse for Reynard studies by medievalists from Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge; two exhibitions at the Bodleian, one on the fox, the other on Anglo-Dutch literary heritage; an inspired prose retelling of the Reynard by Anne Louise Avery; and – with thanks no doubt to Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox of 1970 and the major animation film it was made into in 2009 – two short creative animation films, made by special education needs children, in workshops at the Aardman studios where they were assisted by animation designers and filmmakers.

A first major achievement of this project is the recent scholarly book by Sjoerd Levelt and Ad Putter, with contributions from others, North Sea Crossings, The Literary Heritage of Anglo-Dutch relations, 1066-1688 – a richly illustrated book, shining a new light on cultural exchange, collaboration and mutual impact across the North Sea, between the English and the Low Countries in this key period in European history between the two continental invasions of Britain. This impressive book doubles as the guide to the great exhibition under the same title in which Reynard has a major presence – a major event, running at the Weston Library in Oxford from 3 December 2021 to 30 April 2022.

At the Bodleian, meanwhile, from December 2020 till early January 2021 (though accessible online), a smaller exhibition was held to mark the launch of Avery’s Reynard the Fox, with performances, audio plays, an interview with the author, and a showing of the two creative adaptations made with Aardman Animations – respectively, of ‘The Fox and the Wolf’ (about Sir Isengrim), and of Sir Bruin the Bear and the honey trap.

For her imaginative retelling Avery follows the order of Caxton’s narrative, expanding and embroidering it with lots of medieval Flemish couleur locale – of landscapes, places, walks, local lore on animals (very good on birds), culinary detail, playfully learned notes on ancient books, and living memories (e.g. of the ‘Free Fox of Flanders’). Moving the narrative forward, Avery engages with her readers in a spoken style, with great storytelling, attractive characterisation, brilliantly persuasive speeches, and intensely dramatic entanglements between Reynard and his many enemies at the court of King Noble the Lion.

Events are narrated in long, flowing sentences, using a Caxton-like ‘in-between’ language, a seductive mix of Flemish, Anglo-Saxon, French, Middle Dutch, English and Latin words – rare and ancient or newly coined, all supported with a Glossary of words, supposedly compiled by Reynard’s wife, the linguist and translator Lady Hermeline the Vixen; with a humour and feeling as infectious as T.H. White’s Arthurian romance, The Once and Future King (1958). A major book, for general readers and lovers of literature alike, in a rich and inspired retelling (praised by Marina Warner) that invites rereading. A big book too, ideal for these pandemic times.

As we see, Reynard the Fox is alive and well today, in literature and culture, in society and in our imagination – in new books and exhibitions about him; in the textual scholarship, translations and retelling of his tales; in film, performance and animations of his adventures.

Detail of a bas-de-page scene of a fox, with a mitre and a pastoral staff, preaching to several birds. Source: The Queen Mary Psalter, between 1310 and 1320

Detail of a bas-de-page scene of a fox, with a mitre and a pastoral staff, preaching to several birds. Source: The Queen Mary Psalter, between 1310 and 1320© British Library, London

And all the time, new and different Reynards emerge. Just think of the cynical Machiavellian Reynard of early modern Europe; the revolutionary Reynard of Goethe and Tom Paine in Enlightenment times; our contemporary irreverent bourgeois Reynard of Roald Dahl; the streetwise, rebellious American Reynard of James Simpson; or the titled, aristocratic scoundrel of Avery’s British retelling, with his irrepressible vernacular swagger. We even fleetingly encounter a Spinozist Reynard imagined by Avery, who just follows his foxish nature, in the ancient tradition of naturalia non sunt turpia, where there is ‘nothing to be ashamed of’.

So, what of these different Reynards? Is there a moral here – or, any moral at all? Caxton left this question to his readers, and so does Avery: “each reader has to decide for themselves”. Machiavelli and Tom Paine, on the other hand, do address the matter: be warned, for all the wit and charm of the fox’s tale, the fox is, and will always be, a vicious and cruel animal. Here, as his readers, we do need to consider how Reynard always gets away with his words. What can we, as his readers, learn from this? Is it how, with his words, he pursues his intrigues, always scheming, and playing to the credulity and gullibility of his fellow beings, to their self-interested reasoning, desires and short-sighted greed – so he can dupe them the better with his lies? And isn’t that precisely how he entertains us and takes his readers in?

Reynard the Fox, drawn by Ernest Henri Griset (1844–1907), from a children's book published in 1869.

Reynard the Fox, drawn by Ernest Henri Griset (1844–1907), from a children's book published in 1869.© Wikipedia

Seen in this light, Reynard is the epitome of the spin doctors and media manipulation that dominate virtually everything in our world today. Now, as Saint Augustine said (the sceptical view also of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholia (1621)): mundus vult decipi – ergo decipiatur, that is: the world wants to be deceived – so let it be deceived. But against this, the fox’s tales, for all their brilliance, do remind us that it is vital – essential even, when our survival is at stake – to use our minds, our good sense and critical instincts, so as not to be deceived. Just as Chaucer advised his readers at the end of his Reynard and Chauntecleer:

“But you that think this tale is a trifle

about a fox, or a cock and a hen:

accept the moral, good people.

For Saint Paul says that all that is written

is certainly written for our learning.”

Further reading

- North Sea Crossings. The Literary Heritage of Anglo-Dutch Relations, 1066-1688. Edited by Ad Putter et al. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2021

- Reynard the Fox. Retold by Anne Louise Avery, Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2020

- Of Reynaert the Fox/Van den Vos Reynaerde. Edited by André Bouwman & Bart Besamusca, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009

- A Literary History of the Low Countries. Edited by Theo Hermans, Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2009

- ‘North Sea Crossings’. By Ad Putter & Sjoerd Levelt. Tiecelijn 32 (2019), 40-51

- ‘A Reynard for Our Time’. By Reinier Salverda. The Low Countries vol. 24 (2018), 298-299

- Reynard the Fox. A New Translation. By James Simpson, New York: Liveright